UK/European Powerhouse Grower/Marketer — G’s – Puts Family Farming To Grand Scale And Builds Diverse Business In Countries Around The Globe

July 28, 2020 | 28 min to read

What is it that makes a produce company great? It is a quandary that has been the subject of the Pundit’s reflection since we launched PRODUCE BUSINESS magazine in 1985. We’ve traveled to every continent, save Antarctica, seeking to understand this and, as of now, this is our top five criteria:

1) The company must be willing to innovate. Go new places, try new things and take on the risks that are always part of the novel.

2) The company must have saved its pennies. Great things involve long time frames and some risk. If the company can only do things that will pay off immediately, its prospects are inherently limited.

3) It needs older people and younger people, all with the same level of dedication to the company. That typically means multiple generations engaged with a company.

4) Executives must be committed to study and forward thinking.

5) The company must be willing to try to guide and inform customers, even when they don’t think they have much to learn.

Many companies are successful, but only a few meet these criteria. One company that does happens to be the subject of our interview today. We asked Pundit Investigator and Special Projects Editor Mira Slott to find out more:

John Shropshire, CEO

Chairman

G’s Fresh Ltd

Barway Ely

Cambus

United Kingdom

Guy Shropshire

CEO

G’s Espana Holdings S.L.

Torre-Pacheco, Murcia

Spain

Q: This is a special treat that you were able to juggle your schedules to team up for this interview.

Produce industry executives are wrestling with the twists and turns and unknowns of the global COVID-19 pandemic. And at the same time, we are still wrapping our heads around the pending impacts of Brexit and how that will effect and intersect all aspects of procurement, buying and selling, relationships across the supply chain, etc.

G’s, a truly integrated operation that is large and diverse, brings unique perspective and multifaceted vantage points to the discussion. G’s is a story of incredible resilience and success, even in these most challenging times. As one of Europe’s leading fresh produce companies and most prominent produce families in the UK, G’s supplies customers across the UK, Europe and the U.S. through its farms and production facilities and licenses located throughout the UK, Spain, Eastern Europe,Western Europe, the U.S., Australia, South Africa and Senegal.

Could you walk us through the evolution of your company, how did it start, how did it grow, and the strategies you’ve employed to not only persevere but thrive? Then looking forward, what do you see as the biggest challenges and opportunities…

JOHN: The historical background is my father was one of four boys. One got killed in the war, and the oldest two took over the family business. It was farming and butchering. There really wasn’t room for my father, so he had to find his own way, which was a good thing in a way. He started in the business on his own when he was 24 years old. My father was born in 1925. With adversity comes opportunity really.

Q: Many people have become successful in realizing that… and a fitting mantra for the challenges in this current environment.

JOHN: Yes. So, my father managed to get started on a farm, where the farmer selling the land was very helpful to him because he had limited capital. And then he started growing celery on a small scale. As a teenager, he did work in the family’s butchering business, so he did understand the concept of customers and presentation of product and how to sell it as a marketer. He could see the opportunities of adding value to the celery by prewashing and prepacking it, so that’s what he started doing.

His big breakthrough came in 1961 when Marks & Spencer approached him to actually supply them direct. So, in 1961, he started washing and supplying celery to Marks & Spencer’s. The celery business grew and then he got into other crops. The next big one was onions and doing other crops as well, but celery and onions were the main ones.

Then in the mid 70’s, he made some really big steps. He poured in a lot of money and invested very heavily in new modern facilities and operations to serve the broader supermarket world, because by then it wasn’t just Marks & Spencer but other supermarkets as well. He made very big state-of-the-art investments in facilities.

Celery Harvest in the UK

I joined in the mid-70’s, and my brother in the late 70’s. And since then, we have steadily built the business, through adding new crops. We added lettuce, then we added radish, beetroot, and so on. We continued to add new crops, and also new farming concepts like organic. Well, 17 or 18 years ago, we added organics.

Q: Much has transpired since then…

JOHN: We actually have grown the business now to sales of about £500 million. The biggest factor I think for the growth has been acquisitions we’ve made as we’ve consolidated the industry. We’ve merged with about 25 other businesses over that period. And we’ve also developed partner growers with a cooperative called G’s Growers Ltd. So, we’ve basically merged our businesses with those growers into one organization. It merges farmers through acquisitions with marketing companies, and the two together have enabled us to grow.

Q: How do those sales break down? Are they primarily in the UK market?

JOHN: Of that, about 70 percent of those sales are in the UK — two-thirds of sales, more precisely. The other sales are in Europe and more recently in the U.S.

So, we’ve continued with our original view of focusing on what customers want and adapting to changing markets, and we’ve been looking at ways of adding value, making our products more convenient, whether that’s ready prepared beetroot or ready prepared celery stick packs. But the majority of our business is still the core commodities — iceberg, romaine, onions.

Romaine lettuce crop in Spain

Q: Could you talk more about the vertically integrated aspect and sourcing strategies from a global standpoint.

JOHN: Yes. The way we developed sourcing… in the 80’s the strategy was to build year-round supply for our customers because we felt they were going to need that. Our job is to supply customer needs. It’s not just products; it’s about logistics.

Of course, we went to Spain and started producing, and then we acquired other companies in Spain, some of them very, very big, and we did a consolidation job there as well. And then, of course, we went to Senegal and started producing there in the winter. Producing crops in Senegal is more competitive with certain products.

Q: Which products would those be?

JOHN: Spring onions, what you call scallions. Labor costs are quite high in Spain. Similar to how Mexico supplies scallions into the U.S. market, Senegal supplies scallions into Europe… and then radishes as well.

What’s happened over the past 10 years or more — it could be 20 years now — is my children started coming into the business. My generation — my brother, and my sisters — have worked in the business for periods of times, but my brother and I were basically full time in the business, and then over the past 20 years, my children started coming in. I have three sons, Guy, Charles, and Henry working full time in the business. Guy is the CEO of our European businesses, so he is based in Spain, also overseeing operations in Poland and The Czech Republic.

Guy, do you want to talk a bit about the supply chain and what you’ve done in Spain…

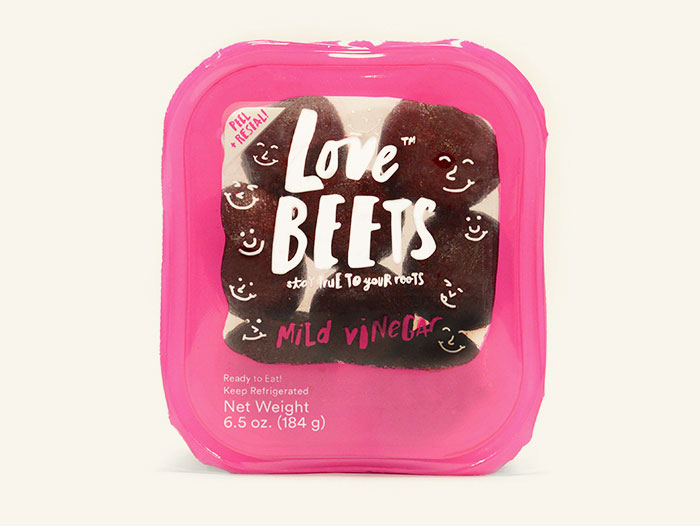

GUY: Just to give you some background, I joined the business 13 to 14 years ago, and for the past 10 years, I actually worked outside of the UK. So, from 2010 to the beginning of 2014, I was in the U.S. working full time for Love Beets, together with my wife Katherine.

Q: Your Love Beets venture took off in the U.S., essentially creating a new market for the commodity by reinventing how Americans typically perceive and consume beets… What was Katherine’s role?

GUY: Katherine was the marketing director, and she was the brand founder in America for Love Beets. She did all the development and marketing of the brand, and social media campaigns. Katherine is the brand ambassador of Love Beets in America.

Then we came back to Europe, directly to Spain, and we’ve now been in Spain for six-and-a-half years. So, my responsibilities include our businesses in Spain, and the Czech Republic and Poland. We also have in Europe a joint venture for beets, and we sell beets product in the U.S. under the Love Beets brand.

Q: How aligned or divergent are U.S. strategies from those in the UK and in European markets?

GUY: The best education I could have for serving the European market was actually the time I spent in the U.S. with Love Beets, because unlike the U.S., the British market is very consolidated and highly organized. Europe is made up of many countries, cultures and consumer taste preferences.

It’s very diverse, and also very fragmented. There are many, many retailers, just like in the U.S. You’ve got your big retailers with market share and operations in a number of markets, but you’ve also got a very fragmented market. Continental Europe and North American markets are similar in that regard. And then you have retailers like Ahold that are huge in Holland and the Benelux regions, and which also has a big presence in the U.S.

Europe is a very large market, quite a lot of people, and it requires different supply chains depending on the countries you’re trying to serve. So, we kind of developed a model that fits with that.

For example, with beets, we’ve set up a factory in Holland to service the Dutch, and German and French markets. We already have a factory in the UK, but in order to serve European markets correctly, you must have a physical presence.

Q: Beyond the supply chain logistics, does your modeling apply to the product development and marketing side? For instance, are you innovating or adapting products and marketing strategies to accommodate different markets and consumer palates? Are consumer preferences in the UK that dissimilar to those in the U.S. or other European markets?

GUY: Yes, that’s a very good question. For example, celery in the UK market is much like in the U.S. — kind of a raw celery market. People eat celery raw as a snack, to dip it, or as a salad topper.

The European market, however, is quite averse to that concept, and celery is a cooking product. Therefore, we created a cost structure in our supply base for celery to meet those divergent market preferences. That’s one example of something we’ve had to do.

We like to do the celery varieties for snacking alternatives here, and predominantly focus on the UK market. That’s not to say we don’t want to create markets where we can act to change consumer trends in eating celery. We’re in the process of development, trying to link celery to other brands, snacking brands, things like soft cheese, hummus, guacamole, etc., to encourage consumers to see celery differently and to see it as a raw snacking item. A lot of efforts are being pushed into that initiative, and that’s just one example.

Q: Your Love Beets initiative encouraged consumers to see beets differently… What was the genesis of that?

GUY: The Love Beets concept was originally developed for the UK market, as private label; in fact, it’s all private label. When we went to the U.S., initially that’s where we innovated the way we packaged and sold product, and the package branding. Since then, we’ve done significant innovation with Love Beets in North America with different recipes and different flavors, beet salads, pico de mayo, beet juice, beet powder… to serve a larger beet market.

In terms of distribution, there was a core market for consumption of beets, which was predominantly canned. What we created was a fresh, convenient category that hadn’t really existed before, so we grew the overall beet category.

The biggest thing we did — other than establish a core market in Wegmans and Whole Foods and some of these smaller independents, some subsidiaries of Kroger, etc. — what we did was really establish core product regions across North America, including Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and Canada and Mexico, so that really was the turning point for our business to grow, and to really expand the category.

Q: I also wanted to ask you about development of your mushroom business…

GUY: John, you answer that one.

JOHN: We had the opportunity to invest in a mushroom marketing start-up… it must be 15 or 16 years ago now. Someone who had been a director at G’s and left and came back with the concept for us to supply Tesco with imported mushrooms, and to provide a direct sourcing model. It wasn’t exactly direct-sourcing, but direct delivery straight from the farms, in Holland and so on. So, supply chain efficiency.

With the great recession in 2008 and 2009, the pound fell very substantially against the Euro, and there was a move in Britain to source more product from the UK. So, we were encouraged by Tesco at the time to actually build a mushroom farm in the UK to bring in more local product to fill their shelves because the UK certainly became more competitive.

Q: How did the arrangement work? Did you have an exclusive contract with Tesco?

JOHN: It was a partnership. We put in all the capital; they didn’t put any capital in, but we did it in conjunction with Tesco as a partner supplier. And they connected to the farm, and we built it in three stages over the next five years. It fit well with our supply chain and it fits in well with the product offerings we have with Tesco.

Q: Have you done other things like that, where you have exclusive arrangements with different retailers…?

JOHN: We have a number of those for different products, where we’ve developed a new product that is exclusive with an individual retailer. For example, originally, we developed flow-wrap celery with Waitrose, and they have exclusivity for that. We’ve had other products with Marks & Spencer’s and Sainsbury’s, where we developed special beetroot items. So, yes, we have a number of examples, where we’ve provided exclusive innovations or new products to our customers for a period of time.

The UK market is more like that and lends itself to customization because it’s not a branded market; we are a private label supplier, so we do work very closely with our customers because of that. So, there are more types of those exclusive arrangements like that in the UK than you would find in the USA. Would that be fair to say, Guy? Would you agree with that?

GUY. Yes. The private labels suppliers tend to innovate and work exclusively with their customers, so to a certain degree that’s true.

Q: Could you share more about your global operations in Poland, The Czech Republic, Africa… joint ventures, licenses, subsidiaries, etc.

JOHN: The Senegal operation… we were actually importing green onions from Mexico, and we were concerned about sustainability and the carbon footprint bringing the product across the Atlantic, and we were looking for an alternative.

There are onions grown in Egypt, and we do source from Egyptian growers, but we were looking for an alternative really, and we continue to do that. Although we have a great relationship with the growers in Mexico, they are very dominated by the U.S. market.

We decided on Senegal because Senegal has the people, and that crop is very labor-intensive. Also, there’s very large areas of land that are not really farmed, and it’s got plenty of water. And also, it’s a democratic state and currently the whole government situation is quite secure.

Q: How complicated was it to develop your farming operation there. Were there challenges with the agricultural infrastructure?

JOHN: We actually invested over £10 million there in Senegal and started up a business basically in the middle of nowhere. There was no electricity, and we made our own bricks and concrete. We built everything ourselves. We employ 1,000 people there.

Q: So, your business in Senegal addresses the three legs of sustainability — environmental, social and economic…

JOHN: You can’t buy land in Senegal. The deal we have with the government is to take the land in return for community benefit. We provide medical facilities and support schools, but most important, what we’re most proud of, for every acre of land we set up for ourselves, we set an acre up for the local farmers. They are subsistence farmers who farm on the edge of the lake. Before we got there, they farmed as close to the lake as they could, so they could actually dig the water by hand.

John Shropshire – Opening a medical Centre as part of a community partnership in Senegal

We built a big canal, over three miles long, and it takes the water out to the local farmers, and then they’re able to farm on a much bigger scale. And they’ve done a terrific job, I have to say.

And the government gave us tax incentives to grow crops for export. They don’t want us supplying the home market because they want their own farmers to supply their own market.

Senegal doesn’t produce enough food, so the country imports a lot of it. The government plan is to get the local farmers to be more productive. So, the local farmers supply to the local market and we sell to export markets, and then the country earns through us the foreign currency and also the job creation of course, with a thousand people.

We have an amazing story of a young Senegalese man, who is now a tractor driver with us, and he trained with us, and is very successful. He was one of the guys who capsized on a boat and was saved by the Spanish navy. He was trying to get into Europe to find work. You may have seen it on the television.

Senegal – John Shropshire, Yatma Fall, Derek Wilkinson (Managing Director, Sandfields Farms Ltd). Yatma Fall capsized in a boat and was rescued. He has been working for WAF (West Africa Farms) since 2012.

Well, you have people coming in from the South and Central America trying to get into the USA for refuge and work… we have a similar situation here in Europe. This man’s life was saved by the Spanish navy, and he was sent back to Senegal to his local village, and that’s where we arrived, so he now has a job and is doing well.

Q: That’s a rousing story. Guy, could you tell us about your work in Poland?

GUY: Poland is a small farming and marketing business that we discovered in that country, and it is run by two senior leaders living there. What I think is more interesting is their story. They started working for G’s in the UK at least 20 to 25 years ago. As seasonal workers while they were at university undergraduate level looking for work, they came over every summer from the age of 18 or 19, and actually cut iceberg lettuce.

And then after graduating, they became full time employees and basically worked their way up through the business from supervisor roles to crop managers to go on to become senior leaders. One is director of all of the farming and harvesting in Poland, and the other is commercial director in charge of all of our sales and commercial marketing, and also runs the cooler and packing operations. So, it’s a very interesting story from that perspective.

The Poland business is relatively small, but it has a huge potential because that’s a growing market — that whole Central European market, the population and GDP, and the rise of Eastern European and Russian markets. When European relations improve with Russia, there is huge opportunity to provide fresh fruit, fresh salads and vegetables. It’s a growing business. In 2015, sales were basically nothing. It’s focused on producing onions, celery and lettuce.

JOHN: In the same way that Guy went to America to start a new business, Guy’s youngest brother Henry went to Poland and started that business.

G’s Poland – Henry Shropshire

Q: You are progressive in terms of seeking out new opportunities… Are there significant risks in taking on some of these ventures, for instance, investing large amounts of capital upfront before you see the return?

JOHN: Yes, for some of them. The Polish business isn’t that big, but it’s still risky. There’s an element of risk in all of them. The Czech Republic business is actually a joint venture with the Valtr family. Tomas Valtr is the managing director of that business and runs it. That has a flower business as well.

Q: This is very interesting to learn the full realm of what you do, and how it connects with what’s happening now with the coronavirus and Brexit, and your strategies for growth…

JOHN: The point about Brexit… you asked earlier if it’s a big issue for us, and it is for me personally, but it’s not a big problem for our business.

Q: Why is that? Does your large, vertically integrated business and global reach insulate you from those problems?

JOHN: The driving force with Brexit is about world trade and local trade, opening up our markets for food from abroad, whereas with fresh produce we’ve already done that. You can’t bring lettuce from Brazil, for example, and you can’t bring lettuce from Argentina, whereas you can bring in beets… So, there’s no real threat for us, and I don’t think things are really going to change.

Q: Doesn’t Brexit effect supply chain efficiencies, logistics, transportation and labor?

JOHN: It’s creating a lot of hassle because we’re coming out of a single market — the lorry comes from Spain and drives all the way to England, Scotland and Wales without stopping. There’s no paperwork, nothing, from one country to another; it’s like the U.S. going from state to state.

Margaret Thatcher introduced the single market; she was the driving force behind it. That started in about 1993. That was the biggest bond fire of regulations and bureaucracy that anybody could ever imagine. And there were huge numbers of people just involved in managing customs, and paperwork. And we got rid of that, and the efficiency is astonishing. So, the danger is to go back to all the paperwork and bureaucracy.

At the end of the day, the customer will have to pay for it. We cannot afford to pay for it because we’re on thin margins. The single market is brutally competitive. Anything that disrupts the supply chain means that import companies like ourselves — the biggest companies especially — will be very well placed to handle all the different complications coming out of a single market.

Companies like us will be fine, but from a political point of view, personally it’s a very bad thing. There’s a lot from our media, at the moment, about importing from America and a post-Brexit/U.S. trade deal surrounding controversies with beef and chicken, but we’re not in that business.

I don’t think we’ll have problems with labor because of Brexit. In fact, I think we’ll be better off because we can go outside of Europe for labor. You know labor was tightening up anyway in Europe. The labor market has constricted over the past few years. With the collapse of communism in 1990, there were tens of millions of people thrown out of work in Europe, so Europe has actually absorbed all those people in the workplace successfully.

That has meant a surplus of labor for the past 30 years because of the collapse of communism. There was a huge amount of people from Eastern Europe who were trying to find work. But most of those people have largely been absorbed. So, what’s happening is there are work programs, like the U.S./Mexico’s H2A guest worker program.

We’re in a similar situation, where countries in Europe are setting up visa worker programs. The UK has a scheme, so does Germany and all these other countries for bringing people outside the EU because the European labor market is tightening up. So, you know, this was going to happen anyway.

Q: How is the coronavirus effecting labor? In the U.S., there’s been a surge in COVID-19 cases of migrant farmworkers, and new coronavirus hotspots in different agricultural production regions.

JOHN: I’ve been watching what’s been happening in America. We’ve been managing the coronavirus very closely. We’ve put very stringent controls in the workplace. We’ve been strictly monitoring staff and workers for health and safety, doing daily temperature checks, and if anyone is showing even the slightest sign of fever, we’ve been isolating them.

Screens in factory (Help prevent COVID-9)

Q: You haven’t had certain hot spots?

JOHN: Britain has one of the highest rates in the world, but fortunately, we’ve been able to contain the virus without too many problems. But Guy can speak of what happened in Spain and how he coped with it, because Spain had very big problems.

GUY: The biggest challenge in Spain was when the government realized they had a major problem in Madrid and Barcelona, two major cities, and they were getting an exponential increase in daily cases. I believe it was on the 13th of March when they took the extremely definitive, but extremely hard decision… literally within a short period of a few hours, the curfew went from essentially completely open with no restrictions to being in a complete lockdown.

And it happened fast. It went from Saturday afternoon being completely free to basically locking down the entire country that same day with the stay-at-home order applying to absolutely everybody with the exception of the essential key industries. And of course, food production was one of those. So, we were able to continue to operate. The problem was the fear created by this very aggressive initiative and hard position taken by the Spanish government.

So, really the biggest challenge for us at the beginning was to get people to come to work because of fear of coronavirus and people dying, and that it was not safe to go to work. We had to very, very quickly set up a sophisticated communication strategy. It was about communicating the facts to all our employees and how we were taking all the right precautions and following the right protocols and actually they were quite safe.

Screens in rigs (Help prevent COVID-19)

We needed to do a job, and we needed to adapt to continue to provide food. The other danger of the coronavirus is recognizing it could lead to starvation. We’ve got to provide food — there’s essential health in food — for Europe. It was that sort of mentality we had to take, and this all happened over a very short period of time. We managed to win the support of the vast majority of our workforce.

Q: It sounds like a very stressful time…

GUY: Yes, it was very intense. There was a lot of fear, and we weren’t really sure what the outcome was going to be. We knew we already had many, many less cases than in the north of Spain, and that our rate of infections was going up significantly slower. We also had the benefit seeing what was happening in Italy, in the south of the country, where there is a lot of population density compared to the more rural areas…

We had to make assumptions in our thinking with our strategies and to clarify what our message was, and the leadership to take with our employees. It’s difficult, because the safety of all our employees is paramount, and to be sure this virus is well controlled and to stop it in its tracks. At the same time, we are an essential industry, not so dissimilar to the healthcare industry, people need us.

Q: In a broader sense, were there challenges in working with customers, and with supply and demand? In the U.S. for instance, restaurants shut down, decimating the foodservice industry, and consumers initially were ravaging supermarket shelves and hording food in anticipation of extended lockdowns…

JOHN: That was the other dynamic at play. At once, we were struggling with the restrictions around social distancing, packing lines, and how to handle equipment, and all of that, which led to significantly less production. At the same time, sales orders from retail, supermarkets, were going up 30 to 40 percent because of the passion buying you described. There was a big challenge in meeting that demand.

Q: Being vertically integrated with diverse sourcing outlets must have really helped…

JOHN: Yes. We relied on our full farming business, which continued, and at the same time we worked with suppliers who had lost business, if they were engaged in the foodservice market, which was significantly limited, to help meet demand. The other big challenge was the availability of trucks and keeping trucks rolling. The majority of transportation companies lost the back leg coming from Europe back into Spain, demand for products brought back started to diminish, so keeping logistic routes open was a challenge.

GUY: At the same time, we had massive rain. The weather couldn’t be worse when the coronavirus kicked off with 10 days of lockdown. We had record levels of rainfall, which further compounded the slowdown in activity, but also impacted employee safety. We didn’t want people getting wet; we didn’t want people working in bad conditions for the risk of increasing the probability of people getting infected with the virus. We got our production down to minimal levels. At least, we could sell the products.

The unsung heroes were the truck drivers leaving their homes in Spain for over a week to bring product to the UK. They were leaving their families worried about them, and there was a lot of media about the spread of coronavirus in Britain.

Q: As a multi-generational family business, how does that shape your business goals and values acumen?

JOHN: We want to be a leading company, one of the industry leaders in Europe, in terms of sustainability, which we’ve worked on for many years. But the next generation coming through is very committed to that. My middle son Charles is very passionate in leading the groups with the sustainability program on farming, the environmental impacts, soil care, and wildlife on the farms.

The industry is always susceptible, isn’t it, with lots of issues of food safety and ethical issues. And we’re dealing with leading retailer brands, and our aim is to support those brands by doing a good job with all those issues. European supermarkets have very, very high food safety standards, and our aim is serving the premium, top end.

Q: Are you involved in programs to alleviate food waste, such as the “Ugly Produce” movement? These types of retail merchandising programs with misshapen fruits and vegetables, while receiving good media attention, have often met with mixed sales results at supermarket chains in the U.S. There’s a debate on what is the ideal amount of food waste and the merits of striving for zero food waste…

JOHN: All the major retailers have value brands. We’ve done a lot of work on food waste, and our retailers are actually encouraging that. The best way, rather than wasting food, is not to produce it in the first place. We’ve done a lot of work on trying to improve our planning and programming, so we grow the right quantity to meet the needs of our customers.

The different brands and specifications have helped a lot. The other thing our customers have done is connected with the ready-meal suppliers, so we are selling some ingredients into the ready-meal industry, and some of our vegetable products have gone into making vegetable juices as well. So, there’s been a lot of work in that area.

Q: You’ve been so gracious with your time and in sharing your myriad insights… to conclude, looking five years down the line, what is your vision for the company and for the industry?

JOHN: that’s one for Guy.

GUY: That’s a good question. There’s what we would like it to be and what we think it will be. From a kind of future food-trend perspective, I think what we’ve seen over past three to five years will continue — transparency across the supply chain, and organic, natural, non-GMO can only get stronger.

If we get in recession, some of these trends will slow down short term, but medium and long term, these trends will prevail, and it’s all around health. The COVID-19 pandemic only reminds us and emphasizes the importance of health and the need to eat well. We’re going to follow that path staying in our full range, healthy salads and healthy snacking alternatives, instead of crisps and chocolate.

Q: I was reading some disturbing statistics about produce consumption in the UK. We have the same challenges in the U.S. With all these healthy eating trends, why do you think it is so difficult to increase produce consumption?

JOHN: It would be an interesting thing for us to study. How much do they spend on advertising in the UK on less heathy food, and how much is spent on fresh produce — there’s nothing really. I was at a conference in January and was asked that question, and during that time, Just Eat was spending tens of millions of pounds on advertising. The advertising budgets for the fast food industry are absolutely enormous.

There is going to have to be government involvement, but there’s a big question of whether they will do that. Our industry is too fragmented. There isn’t the power of one brand. There is no way we can do it on our own. The government needs to take more responsibility.

Q: Initiatives such as Peas Please recognize the imperative of securing a collaborative approach that enjoins common goals of suppliers, retailers and government entities. Maybe it had to take the enormity of a coronavirus crisis and medical outcomes linked to food to finally open that door… A new report, Veg Facts, shows that even before COVID-19, a third of children were eating less than one portion of veg a day, which has just exacerbated during the pandemic, hitting low-income households particularly hard.

JOHN: There’s no doubt about it, there’s a big link between COVID-19 and poor diet and the diseases associated with that… In five years’ time, if we’re not selling more fresh produce as an industry, this will be a massive lost opportunity.

Q: The Food Foundation is calling for a national plan for horticulture:

*The Agriculture Bill must support public health as a ‘public good’

*The Bill must support horticulture as a route to delivering public health

*The Bill must include a requirement for government to report on household food insecurity in the UK

The report also highlights that UK vegetable production fell by 12% between 2017 and 2018, the lowest level of domestic horticulture production for over 20 years. It finds that the UK supplies just 52.7% of veg, with the majority of imported vegetables coming from Spain and the Netherlands.

New research from the SHEFS consortium also shows that the UK is now very dependent for fruit and veg on countries that are at risk of climate change, making supply chains less resilient.

JOHN: As you can imagine, we are hugely in favour of a national plan for horticulture and that the Agriculture Bill puts more emphasis on the role that horticulture can play in supporting both a resilient food strategy for the country and promoting public health.

With regards the drop in production from 2017 to 2018, this was due to it being a particularly dry summer which had a significant impact on the yields. As for the imports from the Netherlands, these are predominantly from indoor production — tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers and mushrooms. During the UK growing season, we are self-sufficient in production of outdoor crops. Spain then fills the gap during the UK off season, not dissimilar to Yuma, Arizona and Mexico for the USA.

From our perspective, with regards the impact of the climate change on the resilience of the supply chain, we don’t see any risk from Spain. In fact it has allowed us to be more productive throughout the winter months as with warmer temperatures, the yields have improved. Evidence would suggest that the weather patterns rotate in 7 year cycles and having had a series of drier years, last year was the wettest on record. Similarly in Spain, there has been significant investment into desal, run on renewable energy, which addresses issues regarding water.

Q: It sounds like G’s is staunchly committed and well positioned to take on the momentous challenges that confront the produce industry today. Thanks for sharing your insight. .

******

We, in the produce industry, have been lucky. As providers of an essential product, we have been spared the lockdowns and almost complete loss of business found in other industries such as hospitality. Some sectors of the produce industry, particularly those heavily dependent on foodservice, have been hit hard, but, in the end, people need to eat and the industry has been fortunate to have customers willing and able to pay for our products in the midst of a global pandemic.

Still, nothing is forever, and as the world changes the produce industry needs companies that are working to grow, innovate and lead. We are lucky to have one in G’s.