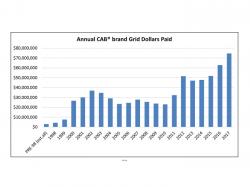

CAB Grids Pay $75 Million Per Year

March 14, 2018 | 6 min to read

Angus producers can increase supply for the world’s leading premium beef brand in just two years—and still earn 44% more premium dollars for the greater supply. It seems to go against the laws of market economics, but that’s what happened from the start of 2016 through last December.

After a long string of sales records that reached 1.14 billion pounds last calendar year, many wondered if Certified Angus Beef ® (CAB®) brand premiums would keep fostering profitability for producers.

A biennial survey of licensed packers, including Cargill, JBS-USA, National and Tyson backs up the brand’s trademark, “the brand that pays.”

At a rate of $8,500 per hour, 24-7, that was $75 million for 2017, up from the $52 million paid in 2015; the linking year came in at $63 million. That brings the 20-year total for CAB premiums to $688 million (see figures 1 and 2), more than half of it paid in the last seven years.

“It started with the believers 40 years ago, but this is how it’s supposed to work,” says John Stika, president of the brand founded as a subsidiary of the American Angus Association in 1978. A foreshadowing of the USDA-reported $14 per hundredweight (cwt.) premium for CAB in one extreme week last year came 30 years earlier, when USDA reported a Colorado packer had bid an extra 50 cents.

Ten years after that, with some 1.5 million head accepted for the brand in 1998, packers were paying $4.4 million per year in specific CAB premiums at $2 to $3 per cwt. on each accepted carcass.

“We celebrated any producer who could make 30% CAB, nearly twice the national average then,” Stika recalls. “Now 30% is the national average and we’re making all beef better.”

Nearly two-thirds of last year’s 4.54 million Angus cattle accepted for the brand sold on packer value-based “grids” that varied widely but averaged more than $5 per cwt. for CAB.

USDA reports premiums paid on negotiated grids, but those make up less than 5% of fed cattle marketed these days. The rest of value-based marketings, about 60% of all fed cattle, sell through what USDA calls “formula pricing,” relying on a base other than spot-price negotiations. Most feeders call it all grid marketing, because all determine value per carcass through premiums and discounts.

Association Board member Dave Nichols, Bridgewater, Iowa, remembers when Ohio-based visionaries started the program.

“Those were really tough times for Angus, when everyone from the ranch to the consumer had bought into the ‘War on Fat’ and the federal government lowered marbling requirement for Choice,” he says. “As a young, performance-oriented breeder, I doubted CAB would succeed but supported it nonetheless.”

Skeptics were everywhere: how could a program that starts with phenotypic screening for a black hide ever hope to pay Angus producers? Carcass specifications were the key, of course.

“Fred Johnson, Mick Colvin and the resolute supporters saw it as the only way to achieve critical mass, to get millions of Hereford cows bred to Angus bulls,” Nichols says. “Astute Angus breeders rose to the occasion by ultrasounding and gathering carcass data to improve the breed, to where now CAB is the gold standard for almost everyone who enjoys beef. This saga is the thing dreams are made of.”

In the 1970s, current CAB Board Chairman David Dal Porto was just starting his herd in the rolling foothills near Oakley, Calif., always supportive of the brand but not directly affected until the early 2000s.

“I saw all CAB did, not just for commercial and seedstock Angus producers, but linking them to feeders,” he says. “We started a relationship with Beller Feedlot in Nebraska and have been feeding high-quality Angus there ever since.”

Annual CAB grid premiums were at a short-term peak in 2002, having increased by nearly five-fold in three years before easing off a bit. That was partly because of less grid marketing and partly because the supply of CAB-accepted cattle was static for the next five years.

The number of those cattle grew 67% in the three years after the Great Recession, but total CAB grid premiums declined in the uncertain times. Then grid marketing took off while the annual inventory of CAB cattle went back to a flat trend through 2015. That squeeze catapulted grid premiums for the brand to double in two years, adding up to more than $230 million in those five years alone.

What’s so unique about the last two years is the simultaneously large increase in both CAB supply and grid premiums, Paul Dykstra says.

The beef cattle specialist for CAB calls it “a remarkable development over the last 10 years.” Consumers realized the value of premium beef in the bleak economy a decade ago when the wholesale CAB cutout price was only $12 per cwt. more than Select grade. Then as all beef prices increased, the Choice-Select spread was slightly wider than the CAB-Choice spread in 2011 and ’13, encouraging more beef marketers to step up to higher quality.

“That’s underpinned by the fact that the Choice share of fed cattle grew from 55% to more than 70% in the last decade while Select fell to less than 20% — yet the Choice-Select spread has averaged greater than $10 for the last two years.” The CAB-Choice spread has been wider in 8 of those 10 years (see figure 3).

Stephen Koontz, Colorado State University professor and cattle marketing analyst, says those factors may help explain why premiums remain strong for top quality beef even as supplies increase, “but it’s too soon to know for sure.”

One thing’s for sure: consumers have changed.

“Right when we had the peak in beef prices, they kind of got tired of paying so much for beef as a commodity, so we had a little demand softness,” Koontz says, “except for the highest quality, which continues to be pursued from foodservice to retail, across the board, especially now that it’s come off the really high prices. They just can’t get enough of the really high quality, and that’s for the entire food sector.”

Some of that is timing, and includes the impact on Baby Boomers reaching retirement age. It could be a demand shift, depending on metrics.

“As a consumer gets a little older and has money, it’s not more beef he’s looking for,” Koontz points out. “Economists measure income elasticity of demand based on how much more we consume when income goes up. I’ll bet the added quantity is not very much, but the quality, that’s where they go.”

Stika notes a University of Missouri model shows premium beef may add $1 billion to the beef economy beyond the commodity level this year. CAB could account for 40% of that, according to 2017 figures for the brand as compared to the overall category.

“That level of business generated in our global economy, through 19,000 partners and their customers, serves as a foundation that will keep generating more premiums,” he says. “With commodity beef, there are winners and losers; at the premium level, everybody’s got to win, many partners, all with an indispensable role to play.”

The shift reaches beyond consumers, Stika says.

“We’ve moved the bell curve in production, with $75 million in CAB grid premiums representing one of the largest market incentives available,” he says. “Some knew since 1978 that this would happen. Then we had pockets of producers who began to realize the profit potential. Now it’s industry-wide, as you can see by the Prime percentage in the mix [quadrupling in four years].”

Can the trend lines keep pointing upward for high-quality beef?

“Keep an eye on two things,” Koontz says. “Exports, because with lots of protein out there, we need some serious pressure relief beyond the domestic market. Secondly, our consumers’ growing preference for high quality has been a driver for the last couple-three years and should be for at least the next couple-three years.”

Older consumers may have started that trend, but Koontz says, “Millennials have decided to go for high quality for their own reasons, from self-professed ‘foodies’ to the growing number who preorder online groceries. As a generation, they have so many boxes they want to check, so many things they want to do, living reasonably but trying a variety of things to find what works.”

Just as beef is not beef, he says consumers are not consumers in this era far removed from anticipating what “your average housewife” will buy, he says. “Sort out consumer groups. Whatever they’re listening to, figure out how to talk to them.”

Dal Porto, the CAB Board chairman, says to maintain leadership in the beef cattle sector, Angus breeders must “constantly improve at every level. We have to offer products that are good for consumers, good for the beef industry and good for the market.”

Source: Certified Angus Beef ® brand